The Hate Studies Symposium was a fairly intimate event. The group of scholars chosen for the event was an interdisciplinary one, although it was weighted towards work on the law and legal issues related to hate, including the keynote speaker Professor Mari Matsuda. The questions we set out to consider were "what do we mean by hate in political discourse?" the definitional problem or challenge and "where does hate come from/how is it sustained?" which leads us to ask "what are the solutions?"

Matsuda's keynote "Is Peacemaking Un-American? On Violence and Ideology" directly addresses some of the concerns that I try to evaluate in my book manuscript and my teaching. She argued that to say "there's no such thing as a false idea" is problematic for a variety of reasons. The notion that all ideas are equally true, based on locating them in the realm of opinion is something commonly seen in American culture, including things as forgettable as this commercial for Elmer's Glue:

"But that's just my depinion" the little girl says, and the assumption is that this is something cute, it's adorable how she uses that adult phrase to refer to glue. But this is a larger claim than just a preference for adhesives, and one that continually causes problems to those who attempt to combat hate speech. If every opinion is equally true, then no opinions can be challenged. It follows from that how no opinions can then be changed. This is what Kwame Anthony Appiah refers to when he criticizes relativism in his book Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. The notion of relativism deployed by "that's just my opinion" shuts down discourse, limits interaction, and sustains false ideas. Matsuda also reminded participants of one of the fundamental arguments behind my research and my spring "Cosmopolitan Imagination" course: literature can humanize the "over there." I look forward to exploring this for a second time with texts like In the Time of the Butterflies, Persepolis, and Interpreter of Maladies.

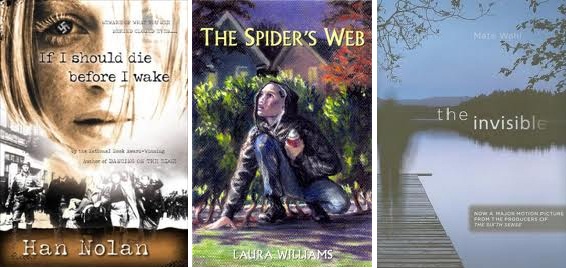

In Faculty Workshop II there were presentations on constitutional histories of lynching from Daniel Kato, legal definitions of hate crimes from Jennifer Scheweppe, and my talk on neo-Nazis in young adult (YA) literature. While these three topics might seem quite disparate, Dr. Robert Tsai (conference organizer) pointed out how the common thread was in considering competence and hate crimes. What does this competence require on behalf of citizens? Who is competent to challenge hate crimes? I would argue that this question of competence could go by another name: empowerment. How can we empower individuals to make good decisions when encountering hate? What sort of empowerment might it take to encourage the idea that we can be wrong, and that's okay? My argument is that literature is one place where we can do this. Humanizing the "over there" is one possible avenue for the humanities and combating hate. Literature can, however, also point us to ways to discuss what Appiah calls "values not worth living by."

|

|

| ||||

| Exterior view of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum. Image courtesy of USHMM. |

This question of privilege is one that the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum skirts, but does not directly address, yet I don't actually know if this particular Museum should be dedicated to interrogating privilege. (Hello, Museum of Slavery, where are you?) This is a conversation that I'm still considering, so please leave comments! Certainly, it asks us to think through why ideas can be false, why values can be wrong, and the extreme example of what happens when false ideas become institutionalized facts about a minority group. Then it asks us to transform that knowledge into testimony, to become witnesses when we were once spectators. I've spent, at this point, years of my life studying the Holocaust and its representations. With all of that knowledge I was surprised at how much the Museum affected me. I don't know what I expected from the experience, and I'm still having a hard time articulating how my expectations and the reality aligned. I was overwhelmed and drained, there's not doubt about that.

I've considered the performative aspects of the Museum before and so was aware of some of the logic behind the space and exhibit planning. In Vivian Pataka's book on theater and the Holocaust she has a excellent chapter ("Spectacular Suffering") covering the USHMM, which I recommend for anyone doing critical work on the Holocaust and memory. As a small sample:

The use of artifacts and dense documentation to produce knowledge and historical presence, and to shape memory, also convey the incommeasurability of the loss by making this density manageable for the viewer. What is critical about the D.C. museum, then, is in its use of small bits of everything--shoes, documents, photographs, artifacts--is the sheer, unbearable magnitude of detail (127).Yet even knowing that, stepping into the elevator holding my ID card (I was a Polish Catholic resistor who survived--several elements that echo my family history accurately) and emerging into the scenes of the liberation of the camps immediately struck me as much more emotionally impacting than I had anticipated. The Museum is dim, laid out to promote reflection, and an example of how architecture can really enhance the experience of the content. It is both a Memorial and a Museum, and not just because it contains the eternal flame and hall of witness. The way the designers used light and space, in addition to content and artwork, was a reminder of how important architecture is. The use of light in the rooms full of pictures from Eisiskes, the path that encourages you to walk through one of the train cars, and the smell of the room of shoes are all the non-verbal performative elements that make it an often-times overwhelming experience.

|

|

I

recoiled at the smell of those shoes. I didn't want to walk through

that train car. I cried (a LOT) when looking at the living faces of the

residents of Eisiskes.

|

| Anne Frank, who would have been 83 this year. Image courtesy of USHMM. |

See my Slideshare lecture from the Hate Studies Symposium HERE.

No comments:

Post a Comment